Ritualized Rager: Partying as Prayer

Even though the modern notion of party has a relatively short history in Iran, Iranians have been partying for a long time. They may have even invented it.

Historical texts like the Tabari and Balaami along with found Zoroastrian manuscripts and accounts by Greek historians like Athenaeus and Polyaenus all describe a rich and elaborate culture of celebration in the pre-Islamic era. In fact, many would argue the empire valued partying and having a good time a little too much.

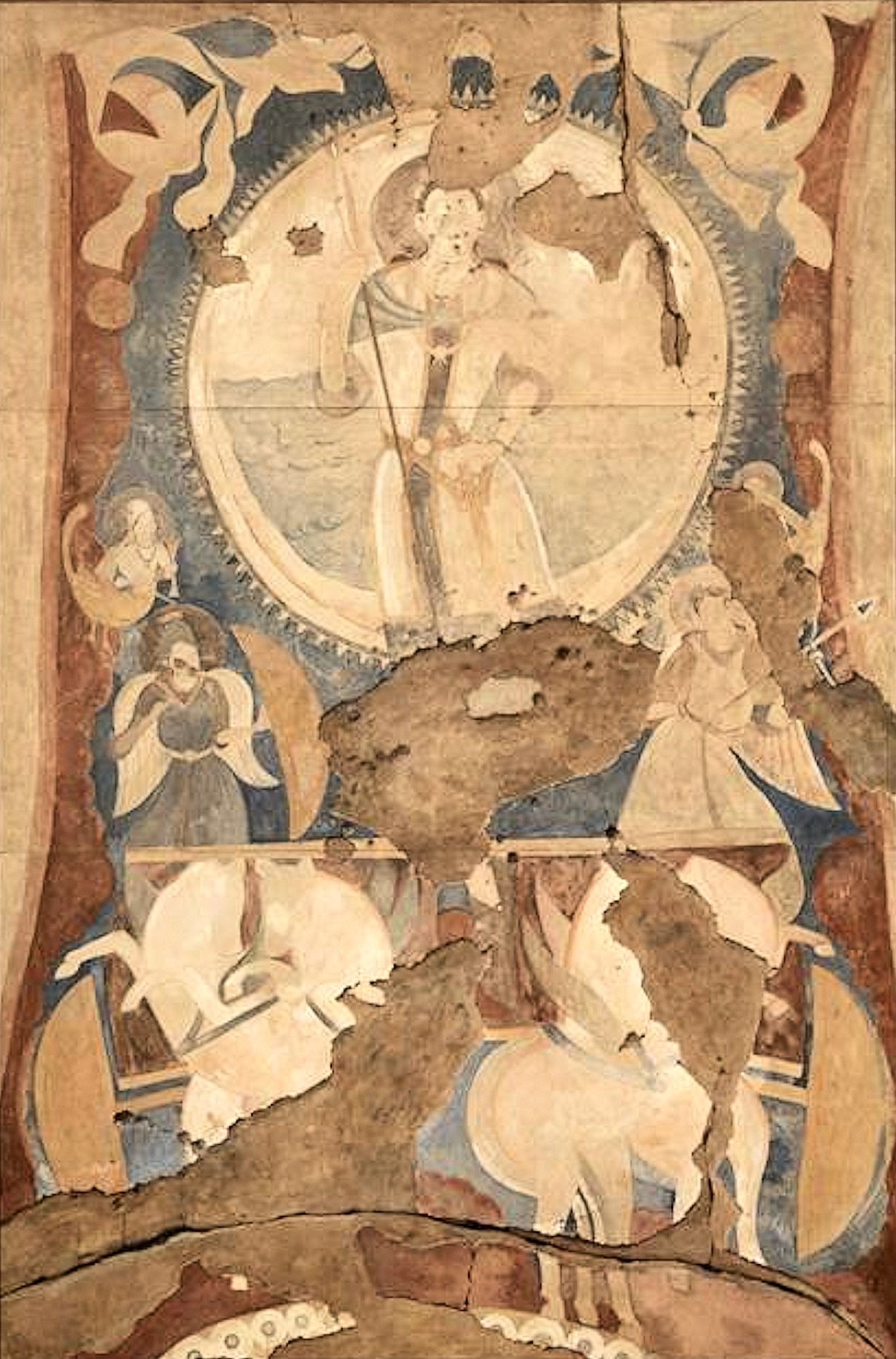

Zoroastrians infamously have numerous festivals and feasts for different deities and occasions during the year. The common term for celebration in modern Persian, jashn is derived from Avestan Yasna, meaning “an act of worship” where a religious service is an essential part of every jashn. There were traditional foods, and some dishes were associated with particular celebrations – wine was regularly drunk, with toasts being given. Male and female musicians are present in the Sogdian wall paintings depicting Zoroastrian banquets. These feasts were sometimes provided by an individual (either through a charitable endowment or by a single act of hospitality) and sometimes — particularly in the case of the Gāhānbārs being the 6 seasonal festivals (5 days each) — communal banquets, with everyone contributing. On top of Gāhānbārs, there are fifteen name-day feasts and six more holy days in a Zoroastrian religious year including Nowrouz and Mehregan.

Mehregan marks the arrival of autumn and identifies with a musical mode. This festival occurs on the day Mehr of the month Mehr, that is, the 16th day of the 7th month. There are different hypotheses about the origins of this festival, especially because the deity Mehr or Mithra dates back to earlier religions than Zoroastrianism. Some also believe Mehregan is celebrated to commemorate the victory of Peshdadian king Fereidoun over the evil Zahhak.